Syed Shayan Real Estate Archive

From Real Estate History

8 Historical Event found

On 27 January 1888, the National Geographic Society was established in Washington DC. The purpose of this institution was to advance understanding of the world’s lands, mountains, rivers, cities, regions, and the human and wildlife populations inhabiting them, and to document this knowledge through systematic mapping. Prior to this, land was generally perceived as a static physical space. National Geographic introduced the idea that land could be measured, recorded with accuracy, and scientifically assessed to determine its most appropriate uses. As a result of this intellectual effort, a clearer understanding gradually emerged of where cities should expand, where roads should be constructed, where agriculture could develop most effectively, and how land value could be determined. In simple terms, National Geographic helped establish the idea that land is not merely soil, but a valuable asset that can be planned, analysed, and managed. In its early work, National Geographic produced accurate maps, conducted precise land measurements, and clarified where the boundaries of regions begin and end. It also explained which land was better suited for housing, which for agriculture, and which for industry or transport infrastructure, a process now understood as land use classification. [img:Images/otd-27-jan-2nd.jpeg | desc:Published by the National Geographic Society, National Geographic represents a benchmark in documentary and research based journalism.These three covers collectively document the magazine’s intellectual progression, tracing its focus from the natural world and wildlife, to human experience shaped by conflict, and finally to contemporary environmental challenges, particularly plastic pollution.Viewed together, they express a consistent archival theme that the Earth, human society, and the environment exist as an interconnected system, each shaping and influencing the other over time.] Once these principles became established, it became easier to pursue planned urban expansion, divide areas into functional zones, and formulate land related laws and regulations. People began to understand why cities often develop near rivers, coastlines, mountains, transport routes, and natural resources, and why certain locations become more important and valuable than others, commonly described as strategic locations. National Geographic further demonstrated that land value is not determined solely by location, but by the characteristics present within it, including water systems, soil fertility, and the availability of mineral resources. This perspective introduced a scientific method for assessing the economic value of land and its investment potential. Later, with the introduction of aerial photography through aircraft, followed by satellite based observation, geographical data relating to land became increasingly precise. On this foundation, modern digital land records and contemporary land administration systems were developed. In essence, National Geographic taught the world that land is not simply a piece of earth, but a geographical asset and a resource based form of capital that can be understood and utilised through informed planning. This approach continues to underpin real estate valuation, urban expansion, and policy formulation today. National Geographic is also widely recognised for its photography, documentaries, and research on animals, forests, land, oceans, and the natural environment. Cartography has remained an important part of National Geographic’s work, an area in which the institution developed considerable expertise over time. Through its globally renowned magazine National Geographic, the Society published maps distinguished by clarity, accuracy, and rigorous research. These maps were not intended for routine government use, but were designed to help readers understand the world, its regions, oceans, borders, and natural systems. As a result, they were widely trusted and used by educational institutions, researchers, and the general public. Although mapmaking was not the Society’s central function, the quality of the maps published in its magazine significantly strengthened its reputation and established it as a serious and credible scholarly institution worldwide. The idea of forming the National Geographic Society emerged in 1888 in Washington DC among a group of geographers, scientists, and intellectuals, most notably Gardiner Greene Hubbard, who became its first president. Their objective was to understand and explain, on a scientific basis, the relationship between the world, land, nature, and humanity. The National Geographic Society is a non profit, public, and educational institution that does not operate under any government authority. Its funding is derived from public donations, membership fees, publishing and media revenue, and research grants. These resources support its staff, research activities, documentaries, and fieldwork. Owing to this autonomous structure, it is widely regarded as an independent, credible, and impartial scholarly institution.

Read More >

On 26 January 1905, the world’s largest known gem quality diamond, the Cullinan Diamond, was discovered at the Premier Mine in South Africa. The find immediately transformed the economic standing of the mine and its surrounding land, elevating the area to exceptional geological and commercial importance. Weighing 3,106 carats, the Cullinan Diamond remains the largest gem quality diamond ever recorded. In 1907, the government of Transvaal formally presented the diamond to King Edward VII as an official state gift. This presentation was duly recorded in British royal and colonial administrative records and was legally recognised as a sovereign and ceremonial offering to the Crown. In 1908, the Cullinan Diamond was cut into a series of royal stones, resulting in nine principal diamonds and ninety six smaller stones. Among these, Cullinan I is the most notable. It is the largest cut diamond in the world and is mounted in the Sovereign’s Sceptre. Cullinan II was incorporated into the Imperial State Crown, where it remains permanently set. [img:Images/otd-26-jan-2nd.jpeg | desc:The diamonds visible in official images from the coronation of King Charles III and subsequent state occasions are prominent components of the original Cullinan Diamond and form part of the Crown Jewels preserved at the Tower of London. The crown shown on the left is the Imperial State Crown, bearing Cullinan II at its front. This stone represents the second largest cut portion of the original diamond and is worn by the monarch during the State Opening of Parliament and other formal ceremonies.The royal sceptre shown on the right is the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross. Set within it is Cullinan I, also known as the Great Star of Africa. As the largest cut gem quality diamond in the world, it is presented to the monarch during the coronation ceremony and stands as a symbol of sovereign authority and state power. (Syed Shayan, Archive Head)] The Premier Mine was located on a Kimberlite pipe. Kimberlite is a deep sourced volcanic rock formed at great depths within the Earth and brought to the surface through ancient volcanic activity. Such formations are known for transporting diamonds and other valuable minerals from the mantle to near surface levels. Kimberlite pipes are extremely old geological structures and occur only in limited regions worldwide. Land containing these formations consequently holds a significantly higher intrinsic and speculative value than ordinary land. In Pakistan, geological evidence of Kimberlite or Kimberlite like formations has been reported in parts of Balochistan including Kharan, Chagai, and Nushki, as well as in sections of the Chitral and Kohistan belts in northern Pakistan. To date, however, no diamond bearing Kimberlite has been confirmed at a commercially viable scale in these regions. Geological assessments acknowledge substantial mineral potential, yet the volume and quality of diamonds necessary to establish these areas as high value mineral real estate have not been demonstrated.

Read More >

25 January 1575 marks the formal foundation of Luanda on the western coast of Africa by the Portuguese explorer and colonial administrator Paulo Dias de Novais. The settlement was originally named São Paulo da Assunção de Loanda, a designation that was later shortened to Luanda. At the time of its establishment in 1575, Luanda was a small colonial port settlement inhabited by an estimated three hundred to five hundred people. Its population consisted primarily of Portuguese soldiers, administrative officials, religious missionaries, and local auxiliaries. The settlement comprised a military fort, limited residential structures, warehouses, and basic port facilities. Its construction was undertaken under the direct patronage of the Portuguese state, supported by military expenditure and driven by long term colonial trade interests. In essence, Luanda was conceived as a strategic state investment intended to secure control over Atlantic trade routes. Over time, this modest outpost expanded into a major urban centre. The Portuguese administration provided the settlement with military protection and a structured system of governance. Gradually, Luanda developed into a principal gateway for trade between Europe and Africa. Warehouses, markets, and residential districts expanded around the harbour, land values increased steadily, and population growth continued. In later centuries, the rise of oil and energy based economic activity further reinforced the city’s importance. As a result, Luanda emerged as one of Africa’s major urban centres and eventually became the capital of Angola. When Angola gained independence from Portugal in 1975, Luanda was already a fully developed administrative, military, port, and economic hub. Throughout the colonial period, government offices, port infrastructure, road networks, residential zones, commercial activity, and international connections had been concentrated in the city. Consequently, following independence, the establishment of a new capital was neither practically feasible nor economically viable. From the outset, Luanda therefore retained its status as the capital of the newly independent state. Luanda can be understood through three interconnected dimensions. At the first level, it functions as the political capital of Angola, housing the presidency, cabinet, military command, foreign embassies, and national institutions. At the second level, it serves as the centre of Angola’s oil based economy, with the majority of national oil revenues, foreign corporations, logistics operations, and financial activities linked to the city. This has shaped Luanda into a rapidly expanding yet high cost metropolitan centre. At the third and most enduring level, Luanda remains a historic port city, continuously connected to global trade networks from the sixteenth century to the present.

Read More >

London:On 21 January 1878, the ancient Egyptian stone obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle formally became part of London’s public and urban landscape. On this date, the monument was opened to the public following its complete installation at Victoria Embankment on the banks of the River Thames. The obelisk was originally created around 1450 BC in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis. It was later presented by Egypt to Britain as a diplomatic gift. Although the transportation of the monument from Egypt to London and its final installation took many years, 21 January 1878 marks the moment when it was officially recognised as a permanent monument on public land in London. At the time, Victoria Embankment represented one of London’s most modern urban development projects. The installation of Cleopatra’s Needle elevated the area beyond its function as a roadway and riverbank, transforming it into a site of historical and cultural significance and enhancing the symbolic value of the surrounding land. In ancient Egyptian civilisation, the obelisk represented royal authority, state order, and religious belief. It was created during the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III, and its inscriptions commemorate powerful rulers, their military victories, and their association with the gods. Such monuments were traditionally erected in major cities and royal or religious centres to publicly assert the authority and prestige of the state. The monument became known as Cleopatra’s Needle because, in antiquity, it was relocated to Alexandria and placed near a site believed to be close to Cleopatra’s palace. Later European visitors were more familiar with Cleopatra than with earlier pharaohs and began referring to the obelisk by her name. In reality, Cleopatra neither commissioned the monument nor had any direct association with it. The name endured due to its familiarity and association with a well known historical figure and was later retained in London and other countries.

Read More >

Although Thomas Edison had already developed the electric light bulb in 1879 and had illuminated public spaces on a commercial scale in New York through the Pearl Street Power Station in 1882, the use of electricity at that stage remained limited to a small number of buildings and confined areas. On 19 January 1883, in the town of Roselle, New Jersey, electricity was supplied to an inhabited community through an overhead wiring system using pole-mounted cables. Under this arrangement, the First Presbyterian Church of Roselle became the first public building to be illuminated, with Edison himself present to supervise the installation. This demonstration conclusively proved that electricity was no longer restricted to laboratories or isolated facilities, but could illuminate homes, streets, roads, and marketplaces after dark. Until then, underground wiring had been prohibitively expensive, limiting access to electricity largely to affluent individuals or select commercial institutions. Overhead wiring, by contrast, offered a far more economical and scalable solution. Edison’s true significance lay not merely in the invention of the electric bulb, but in his capacity to transform that invention into a functioning urban system. While Nikola Tesla possessed revolutionary concepts for transmitting electricity over long distances, Edison was the first to present a practical, working model that carried electricity out of experimental settings and into populated urban neighbourhoods and ordinary homes. Edison did not invent a bulb in isolation. He unified electricity generation, transmission, measurement, and safety into a coherent system that enabled society to move beyond darkness. He understood that a bulb, without electricity available inside homes, would remain little more than a novelty. Once the bulb had been created, the real challenge before him was the establishment of a complete system for the production, transmission, and distribution of electricity. [img:Images/otd-19-jan-2nd.jpeg | desc:These two images depict, with historical authenticity, the town of Roselle in the US state of New Jersey and a public exhibition of the complete early electricity supply system. Roselle is the settlement where, on 19 January 1883, electricity was first delivered to homes through Thomas Edison’s overhead wiring system, while the exhibition image presents Edison’s entire electricity supply framework, including bulbs, wiring, and related equipment, as it was displayed to the public.] Guided by this understanding, Edison turned his attention to power stations, wiring infrastructure, and distribution networks, ensuring that electricity did not remain the privilege of laboratories or wealthy elites, but became an integral part of everyday urban life. Historians broadly agree that Edison’s principal achievement was not the invention of the bulb itself, but the creation of a system capable of delivering electricity reliably and safely. Edison transformed electricity from an isolated invention into an organised grid system. He developed electric meters, fuses, switches, generators, and all essential components of distribution, without which electricity could never have entered common use. This vision first took concrete form in 1882 with the Pearl Street Power Station in New York, which demonstrated for the first time that electricity could be generated at a central location and distributed via underground cables across an entire urban block. This model subsequently became the foundation of modern power grids worldwide. The later experiment with overhead wiring in New Jersey marked another decisive advance. Installing cables on poles was both more economical and more effective for extending electricity to distant urban areas. Electricity was no longer confined to a handful of large residences, but spread into ordinary streets and neighbourhoods, becoming a fundamental element of modern urban life. Through Edison’s sustained efforts, electricity reached a stage at which it could be generated, measured, distributed in units, and sold at a defined price.

Read More >

On 10 January 1992, the formal construction of the Lahore Islamabad Motorway M2 was initiated in Pakistan. On this date, the project was officially launched and approved at the government level. This project proved to be the starting point of the modern motorway network concept in Pakistan. The Lahore Islamabad Motorway M2 was the country’s first fully developed motorway, bringing international standards of road construction, safer travel, and long term infrastructure planning into the national development agenda. The Lahore Islamabad Motorway M2 project was launched during the first term of Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif. Construction was undertaken by the South Korean company Daewoo Corporation on a design and build basis. The motorway is approximately 367 kilometres in length, with an estimated total cost at the time of around 23 to 25 billion rupees. Although the project remained fundamentally a Government of Pakistan initiative, Daewoo did not act solely as a contractor. It also provided financial support through supplier credit and contractor financing arrangements, which enabled the project to be completed within the planned timeframe. In subsequent years, long term concession agreements were concluded with Daewoo for the operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation of the motorway, under which toll revenues were used to recover costs and investment. The launch of the motorway brought a significant transformation to Pakistan’s real estate geography. Planning for housing schemes, industrial zones, service areas, and commercial centres began along the motorway corridor, leading to a marked increase in land use intensity and land values in surrounding areas. Rural and semi rural zones around motorway interchanges rapidly experienced urban expansion, with residential developments accompanied by warehouses, logistics hubs, and industrial units. Improved accessibility and reduced travel time encouraged investors to move beyond the pressure of major cities and towards long term investment in motorway linked locations. As a result, land gradually shifted from agricultural use to commercial and residential purposes. This process not only increased land values but also played a fundamental role in reshaping population distribution and expanding economic activity. The M2 motorway reinforced the idea that infrastructure is not merely a means of transportation but a key driver of land value appreciation, urban expansion, and economic growth. At the state level, it helped establish the understanding that major highways do more than connect cities. They give rise to new urban centres, industrial zones, and real estate markets. In later years, motorway, expressway, and bypass based development projects across Pakistan were planned using this very model. The Lahore Islamabad Motorway was formally opened for public use in November 1997.

Read More >

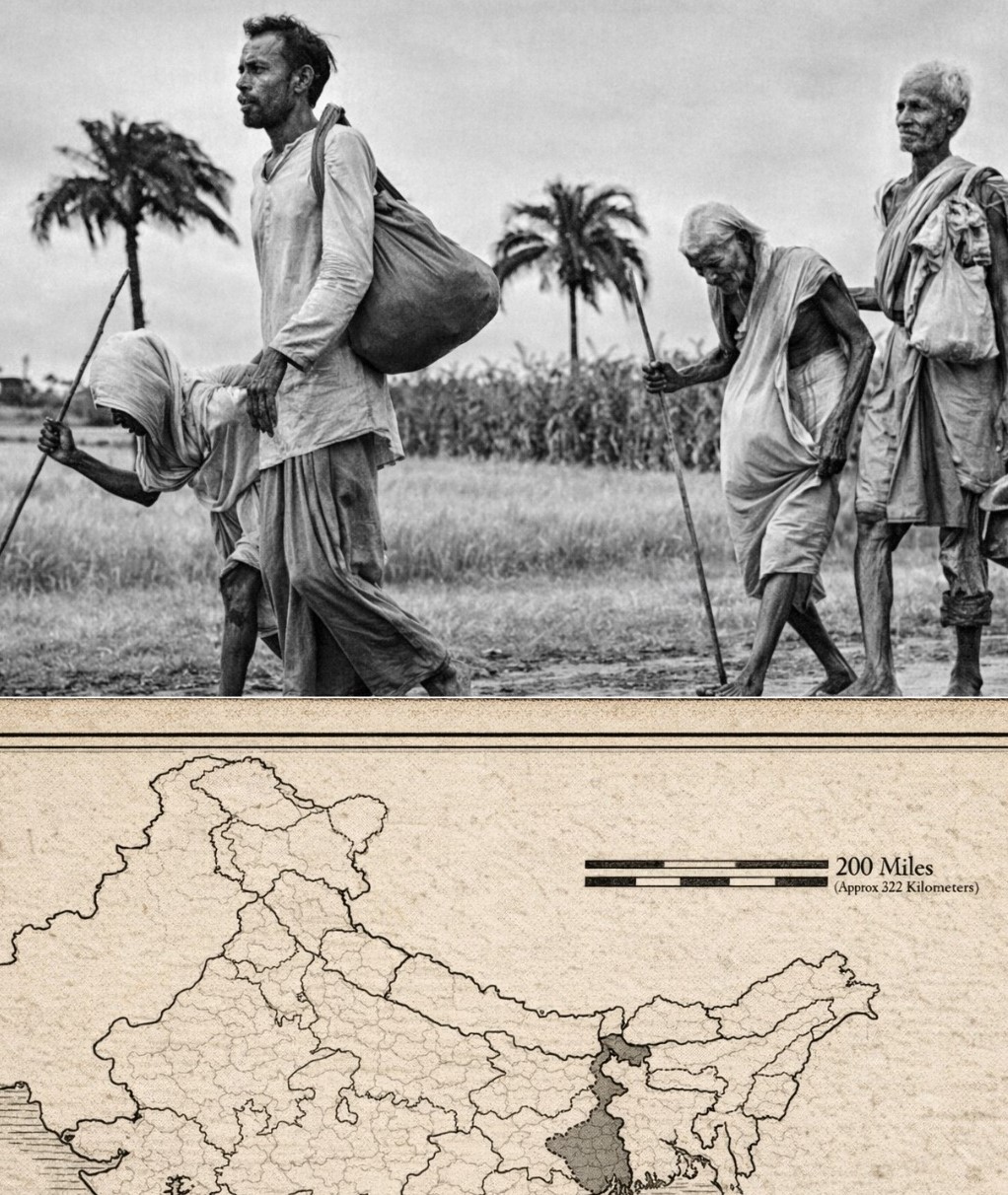

In 1947, the partition of the subcontinent divided Bengal into two parts, West Bengal and East Bengal, later known as East Pakistan. The system of land ownership had been severely disrupted. Large scale migration left millions of acres of land without resident owners, as many had crossed the newly drawn borders. These abandoned properties quickly attracted organised attempts at unlawful occupation. To address this critical situation, the Government of West Bengal took a major administrative decision on 2 January 1948. On that day, all district officers were directed to carry out immediate surveys of land belonging to displaced owners and to place the records under official supervision, ensuring that such properties could not be illegally sold or transferred. Under this notification, systematic ground surveys of abandoned and disputed properties were launched, and the process of land registration was brought under organised state control. This marked the first serious effort by the post Partition administration to restore and restructure land records. A significant feature of this initiative was the introduction of safeguards for sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Legal protection was extended to cultivators who worked land owned by others, ensuring that migration or changes in ownership did not result in their sudden displacement. The notification therefore represented not merely an interim administrative measure, but the starting point of broader agrarian and land reforms. The principal beneficiaries of this decision were poor farmers and tenants who had cultivated these lands for generations. On 2 January, the government made it explicit that no cultivator would be evicted until new ownership documentation had been formally prepared. This measure not only curtailed unlawful occupation but also reassured ordinary people that their primary means of livelihood, namely land, would remain protected. In doing so, it weakened long established feudal landholding structures and laid the foundation for an organised and state regulated land record system. Although the decision initially took the form of an administrative order, it later served as the basis for comprehensive land ownership legislation. Land experts and historical studies confirm that January 1948 marked the beginning of formal recognition of the cultivator as a legitimate stakeholder in land rights. To this day, the events of that period are regarded as a milestone in the evolution of land record accuracy and the functioning of the revenue administration system.

Read More >

Across Pakistan, 31 December is designated as the annual Close of the revenue system, under which all land and property related records maintained by the Board of Revenue are formally closed on a yearly basis. This process encompasses all administrative levels, from the traditional patwari system to modern computerised land record offices. On 31 December, land mutations, the Jamabandi or Record of Rights, and other entries are given final form on an annual basis, while revenue related accounts including land revenue and water charges are closed and carried forward into the new year. Within the revenue system, the most prominent symbol of this day is the Lal Kitab, regarded as the fundamental and classical register of the patwari system. The Lal Kitab records information relating to the nature of the land, natural conditions, crop status, and agricultural resources of the area, details that are not ordinarily included in standard registers. At the end of the year, the renewal of this record is informally understood as a summary of the land’s History of Title. According to our real estate analyst, this annual closure on 31 December is of particular importance for investors and developers, as it forms the basis for determining the legal status of land, tax liabilities, and revenue assessments for the coming year. It is at this point that the previous year is formally closed in terms of land records, and the new year begins with fresh entries. Revenue officials state that although Pakistan’s financial year commences on 1 July, within the land record and patwari system 31 December continues to be regarded as a practical deadline, reflecting an administrative continuity that extends back centuries. Digital land ownership records, both in Pakistan and in many parts of the world, are also frozen on 31 December, and at midnight a new register or digital database is opened for the following year. This process is significant as it determines the total value of land ownership transferred over the course of the year.

Read More >