Syed Shayan Real Estate Archive

From Real Estate History

3 Historical Event found

One hundred years ago, on 16 January 1926, leading English language newspapers published in Bombay, including The Times of India, Bombay Chronicle, and The Bombay, reported on an official debate held during a major government session in British India. These reports recorded that the Bombay Legislative Council had engaged in a detailed discussion on the inquiry report relating to the Back Bay Reclamation Scheme. (The term “reclamation” refers to the engineering process through which a portion of the sea is scientifically converted into new, usable land for residential, commercial, or public purposes.) The meeting took place in the Bombay Legislative Council, where members raised serious concerns about the increasing financial deficit of the scheme and the principles by which land reclaimed from the sea should be valued. Fundamental questions were formally placed on record, including whether reclaiming land from the sea was financially justified, whether such land could possess a sustainable market value, and whether public funds should be committed to the project. Several members of the Council described the scheme as an example of excessive expenditure and a potential misuse of public resources. Concerns were also expressed as to whether the land obtained through reclamation would be capable of recovering the substantial costs incurred in its development. During the proceedings, key findings from the inquiry report were presented, covering financial planning, engineering costs, and projected revenue from the future sale or utilisation of the reclaimed land. A number of members characterised the scheme as one of the most controversial and expensive urban development initiatives undertaken during the period of British India. The marine reclamation works carried out during the 1920s, while not based on modern technology, were regarded as among the most advanced engineering practices of their time. The project involved the construction of robust sea walls and stone embankments along the coastline to withstand wave action and tidal pressure. Sand and soil were dredged from the seabed and deposited through hydraulic filling, after which the land was allowed to settle naturally over several years so that excess water could drain and the soil could stabilise. Where construction was intended, deep timber and early concrete piles were driven through soft layers to reach firm strata below. Although computer modelling was not available, British engineers relied on prolonged observation of tides and coastal currents, supported by manual calculations, to design the works. As a result, despite early apprehensions, the reclaimed areas gradually stabilised and, in subsequent decades, came to be regarded among the most valuable urban real estate in the world. At the time, reclaiming land from the sea for urban and commercial use was considered a novel and unconventional idea. Many viewed it as expensive, risky, and administratively complex. However, later developments demonstrated that the scheme fundamentally transformed the city, led to exceptional increases in land values, and contributed significantly to Bombay’s emergence as a globally important centre of real estate and economic activity. [img:Images/otd-16-jan-2nd.jpeg | desc:What was once seen as an administrative burden later became the city’s greatest asset. Land reclaimed from the sea went on to shape its economic identity, carrying institutions, homes, and values that define the city today.] Although initially regarded as an administrative and financial concern, the reclaimed lands later became some of the city’s most valuable urban properties and formed the foundation of its international economic identity. Areas such as Nariman Point, Marine Drive, Cuffe Parade, Colaba, and Churchgate are all situated on land reclaimed from the sea and today accommodate major financial institutions, corporate headquarters, high rise residential buildings, and some of the most expensive urban properties in Asia.

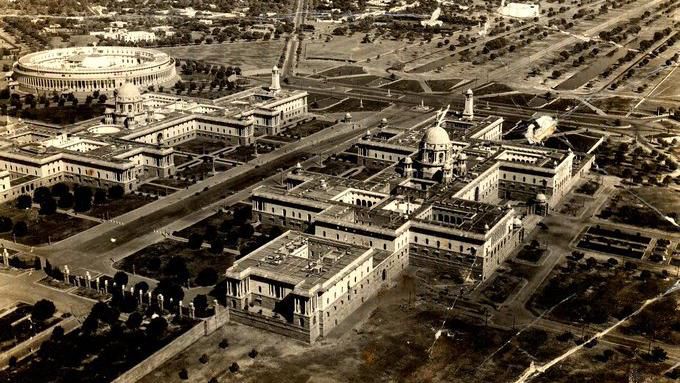

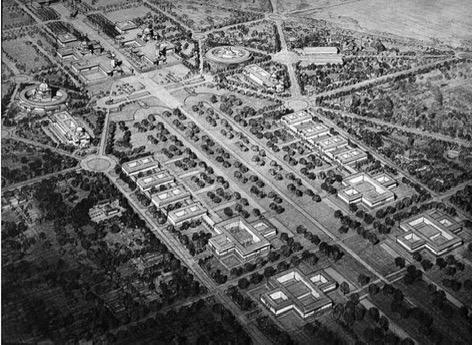

On 21 December 1911, during the period of the British Raj, a formal notice for the acquisition of land for New Delhi was published in the Punjab Gazette. This notification was issued only nine days after the proclamation of 12 December 1911, when King George V of Britain announced the transfer of the capital of British India from Calcutta to Delhi. Through this notification, the systematic acquisition of several thousand acres of agricultural land situated to the south west of present day Delhi formally commenced. These lands were subsequently developed into the core of New Delhi, upon which were constructed the Viceroy’s House now known as Rashtrapati Bhavan, the Parliament House originally called the Council House, the Central Secretariat comprising the North Block and South Block, as well as other major administrative and defence buildings that symbolised imperial authority. To connect these monumental structures, a grand ceremonial avenue later known as Rajpath was laid out, and for commemorative purposes the India Gate memorial was erected. Under the same planning framework, Connaught Place was designated as the principal commercial district of New Delhi, where banks, insurance offices and retail commercial activities were concentrated. In parallel, residential areas such as the Lutyens’ Bungalow Zone, Civil Lines and Karol Bagh emerged as planned neighbourhoods for the Viceroy, senior colonial officials, members of the civil services and the urban middle class. All these measures were undertaken under the provisions of the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, enabling the legal acquisition of land for public and governmental purposes and laying the organised urban and real estate foundation of the new imperial capital of British India. Following the announcement of the capital’s relocation, the British administration moved swiftly to advance the land acquisition process by issuing the Punjab Gazette notification of 21 December 1911, under which land values were fixed as of that date to ensure that agricultural landowners received compensation prior to the transfer of possession. As a result, lands belonging to Malcha, Raisina and other neighbouring villages were acquired, areas upon which the Parliament House, the Presidential Estate and numerous other key government buildings now stand. This historical event occupies a significant place in the history of real estate, as it marked the formal legal commencement of the largest land acquisition undertaken during the British period in the subcontinent and the construction of a new imperial capital. It not only transformed urban planning and land values but also exerted lasting influence on land use patterns and the spatial hierarchy of cities in the decades that followed.

On 29 November 1912, a decisive notification was published in Part One of the Government of India Gazette, establishing the legal basis for the large scale acquisition of government land required for the construction of New Delhi, the new capital of British India. This notification followed the Delhi Durbar of 1911, during which King George V announced the transfer of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi. The British administration was therefore required to identify an appropriate site and secure the necessary land without delay for the establishment of the new city. According to the notification, and under Sections Three and Six of the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, the southern suburban districts of Delhi were declared compulsory acquisition zones. These included extensive tracts covering Raisina Hill, Malcha, the Revenue District of Mehrauli, and areas extending to the western bank of the River Yamuna. The land identified for acquisition comprised all those areas selected for the Viceroy’s House, the Central Secretariat, the Civil Lines extension, the Central Avenue, and the wider administrative framework of the proposed capital. The notification made clear that New Delhi was not intended merely as a political centre, but as a modern, comprehensively planned urban seat of government, designed to accommodate administrative institutions, major boulevards, residential settlements and commercial districts. Government records indicate that the land being acquired consisted largely of agricultural fields, woodland tracts and small rural settlements. These areas were incorporated into a consolidated urban scheme in accordance with the recommendations of the Town Planning Committee of 1912. Through this notification, the Collector of Delhi was instructed to carry out all requisite procedures without delay, including land surveys, demarcation, mapping, valuation, verification of local records and completion of acquisition proceedings, to ensure the timely construction of Lutyens Delhi. Lutyens Delhi refers to that part of New Delhi designed by the British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens. This area includes major government buildings such as the Viceroy’s House (present day Rashtrapati Bhavan), the Parliament House, the North Block, the South Block and the Central Secretariat. Its broad avenues and ordered urban layout continue to form the core of New Delhi’s administrative identity. The Gazette notification of 29 November 1912 occupies a foundational place in the history of land acquisition, urban planning, colonial architecture and state control of territory in the Indian subcontinent. These official British government records are preserved today in the National Archives of India and the India Office Records at the British Library, where the proceedings of 29 November 1912 are recognised as the formal beginning of the construction of New Delhi.