Syed Shayan Real Estate Archive

From Real Estate History

4 Historical Event found

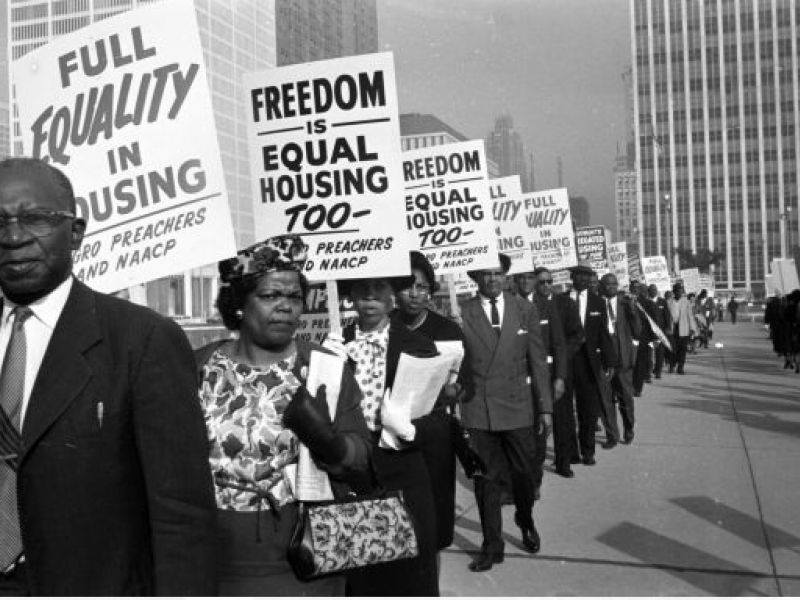

On 5 December 1957, New York City became the first city in the United States to enact legislation prohibiting racial and religious discrimination in the housing market. On this date, the New York City Council approved the Fair Housing Practices Law, which made it unlawful to discriminate in the sale, purchase, or rental of housing on the grounds of colour, race, or religion. The necessity for this legislation arose in the period following the Second World War, when racial and religious discrimination had become entrenched within the housing markets of major American cities. Property owners and real estate agents routinely prevented African American residents, Jewish families, and other minority groups from purchasing or renting homes in certain neighbourhoods. This practice led to the emergence of segregated residential areas and exposed a fundamental contradiction within American society: citizens were legally equal, yet denied equality in access to housing. This persistent injustice, combined with the growing civil rights movement, made the introduction of fair housing legislation both urgent and unavoidable. The decision represented a significant milestone in the history of civil rights in the United States. For the first time, a major city adopted a clear and formal legal position against discrimination within the private housing sector. The law provided statutory recognition to the principle of fair housing and formally aligned the housing market with broader commitments to social equality and civil rights. Later in December 1957, the legislation came into force as a local law. Nevertheless, in historical and policy terms, 5 December 1957 is recognised as the moment when New York laid the foundation for the legal prohibition of discrimination in housing. In subsequent years, this law served as an important precedent for fair housing legislation across the United States and influenced reforms introduced at the federal level.

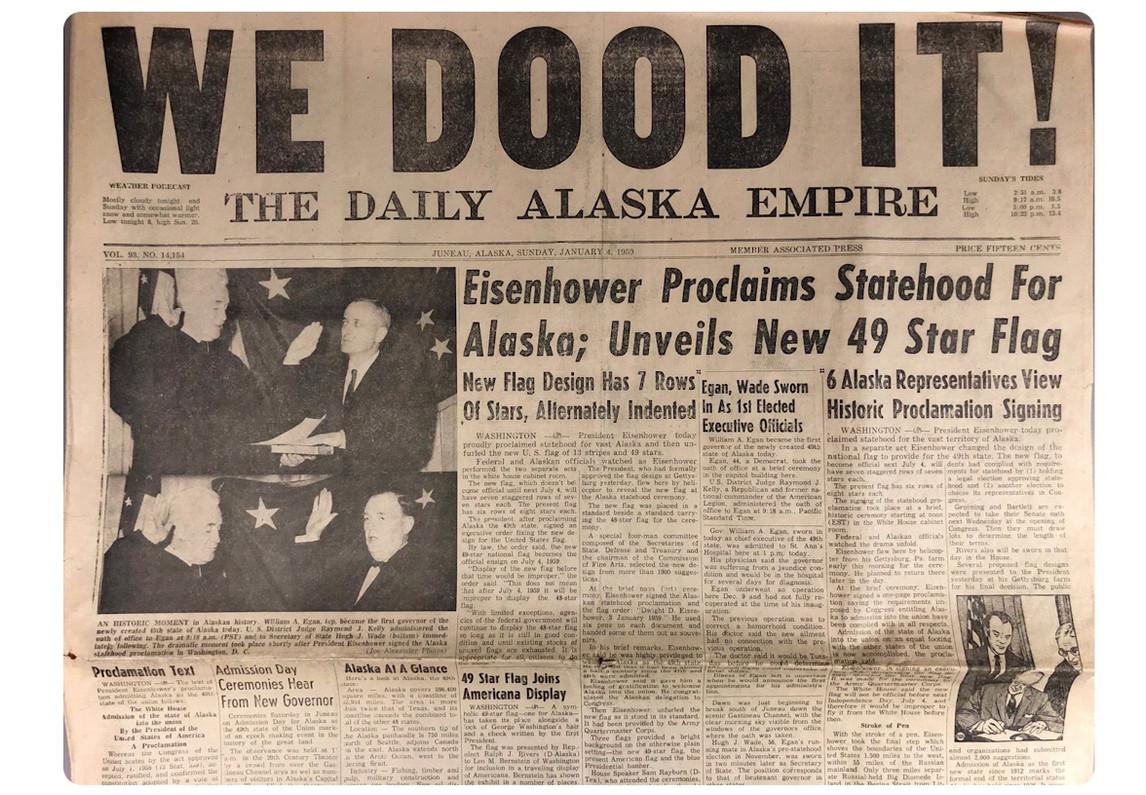

3 January 1959 marks not merely the admission of Alaska as the forty ninth state of the United States, but a historically significant moment representing the transfer of ownership of one of the largest landmasses in modern history. Prior to attaining statehood, Alaska formed part of the Russian Empire and was known as Russian America. Russian explorers first arrived in the region during the eighteenth century, with their primary interest centred on the lucrative fur trade. Over time, however, this trade declined steadily, reducing the region’s economic value for Russia. Given Alaska’s extreme geographical distance from the Russian mainland, its administration and defence became increasingly costly and impractical. These challenges were compounded by concerns that, in the event of a conflict, Britain, then in control of Canada, could readily seize the territory. Under these circumstances, Russia concluded that selling the territory to a friendly power would be the most prudent course of action. Consequently, in 1867, Alaska was sold to the United States for a sum of 7.2 million dollars. At the time, the agreement was widely criticised within the United States and derisively labelled Seward’s Folly, after the then Secretary of State, William H. Seward, who negotiated the deal. In later years, however, the discovery of gold, oil and other valuable natural resources transformed this transaction into one of the most advantageous territorial acquisitions in recorded history. Alaska covers a total area of approximately 375 million acres. With the granting of statehood, the Alaska Statehood Act introduced an unprecedented provision under which the new state was authorised to select and acquire approximately 102 to 103 million acres of federal land. Never before in American history had such an extensive transfer of land been executed under a single legal framework. This decision laid the foundations for structured urban infrastructure, town planning and commercial zoning during Alaska’s formative years as a state. [img:Images/3-jan-2-otd.jpeg | desc:Alaska Territorial Gov. Bob Bartlett in center, with the 49-star flag (Bartlett was one of Alaska’s first U.S. senators).] Before statehood, the value of Alaska’s land was largely associated with gold mining and a limited range of mineral resources. After 1959, however, systematic government surveys, land leasing policies and formal land selection processes brought the region firmly into the focus of investors. Just a few years later, in 1968, the discovery of vast oil reserves in the Prudhoe Bay area fundamentally redefined the economic significance of the land. A barren and frigid region long considered unsuitable for large scale use suddenly emerged as a centre of global energy production. This transformation elevated Alaska’s commercial land to strategic value measured in trillions of dollars. Following statehood, federal funding accelerated the development of infrastructure, leading to a substantial and decisive rise in land values. Major urban centres such as Anchorage witnessed the establishment of planned housing developments, encouraging organised urban expansion and residential growth. Similarly, the expansion of residential and commercial construction in Fairbanks stimulated economic and social activity in northern regions, improving living standards for local communities and contributing to the state’s overall development. The construction of roads and transportation networks made previously inaccessible land usable, overcoming geographical barriers that had long restricted development. Statehood also gave rise to significant disputes over land rights, as the historical claims of Indigenous populations conflicted with federal and state land selection processes. To address these issues, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was enacted in 1971, under which approximately forty four million acres of land were transferred to Native tribal corporations.

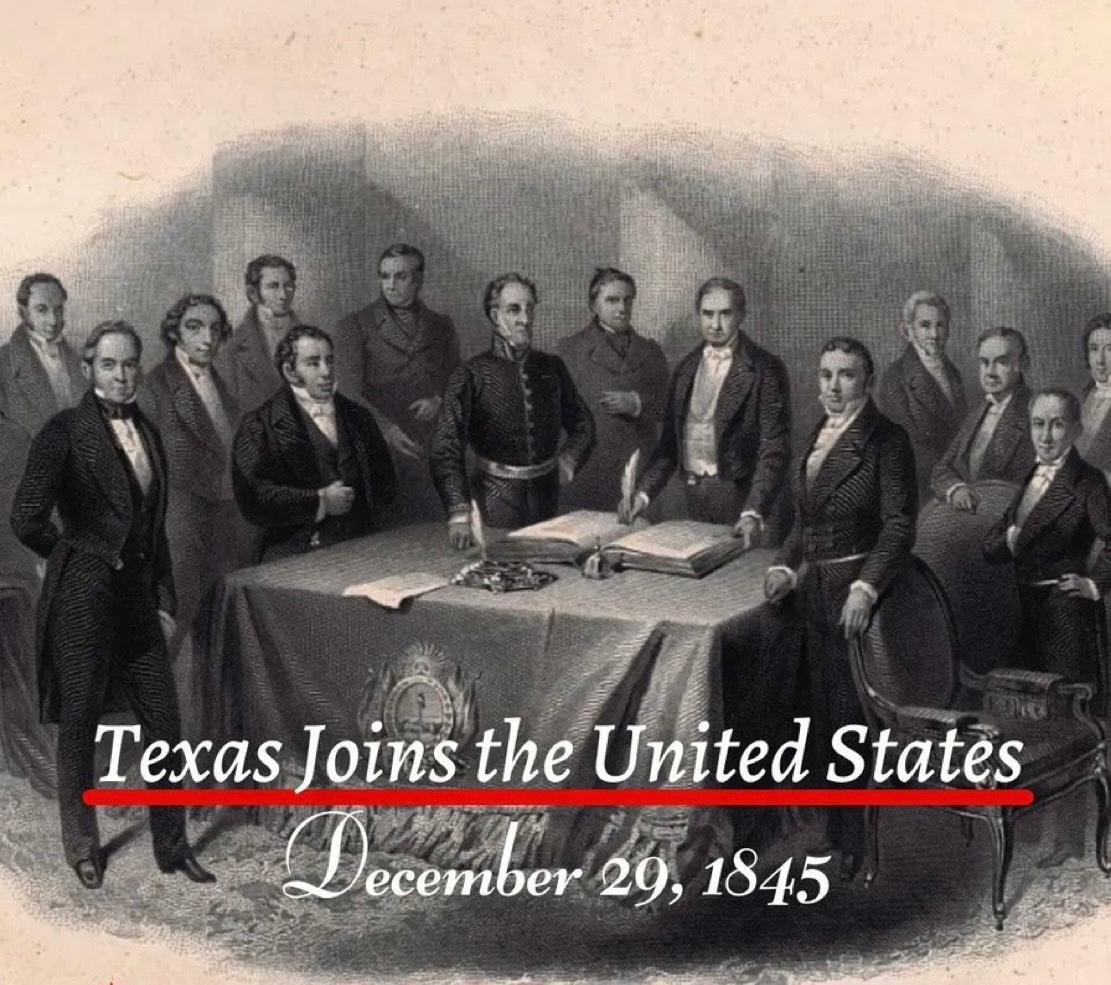

On 29 December 1845, Texas formally became the twenty eighth state of the United States. This event was not merely a political decision. It marked an extraordinary turning point in the global history of land ownership and real estate. As a result of this single day’s decision, approximately 259000 square miles, or nearly 695000 square kilometres, came under the jurisdiction of the American federal system. Texas held a unique position because it had previously existed as an independent republic. The land was already settled. Agriculture was actively practised. Claims of private as well as communal ownership were firmly in place. When Texas was annexed by the United States, all these lands were brought under the American constitutional and legal framework in a single moment. This transition reshaped land registration, land claims, agricultural ownership, and future urban planning within an entirely new framework influenced by American legal culture. Concepts of ownership, legal documentation, boundary demarcation, and patterns of urban expansion shifted from local traditions to align with the federal American system. The historical importance of this annexation is further underscored by the fact that it represented the largest territorial addition ever gained through the admission of a sovereign state into the United States. At the time, the area exceeded that of several European countries and opened the path for the expansion of the American property market towards the southern and western regions. In subsequent decades, these lands formed the foundation for vast agricultural estates, railway networks, industrial centres, and newly established cities. One of the most significant outcomes of Texas’s annexation for the United States was the acquisition of an extensive coastline, providing strong and direct access to the Gulf of Mexico. This geographical transformation also produced a broader economic benefit for landlocked states. The development of ports along the Texas coast created new and more accessible routes for the agricultural and industrial output of inland regions to reach global markets. Over time, as expansive railway networks and integrated river systems connected these landlocked states to the Texas coastline, interior regions became part of the global trade system. In this way, the annexation of Texas emerged as a gradual yet profoundly significant milestone in the overall economic growth of the United States.

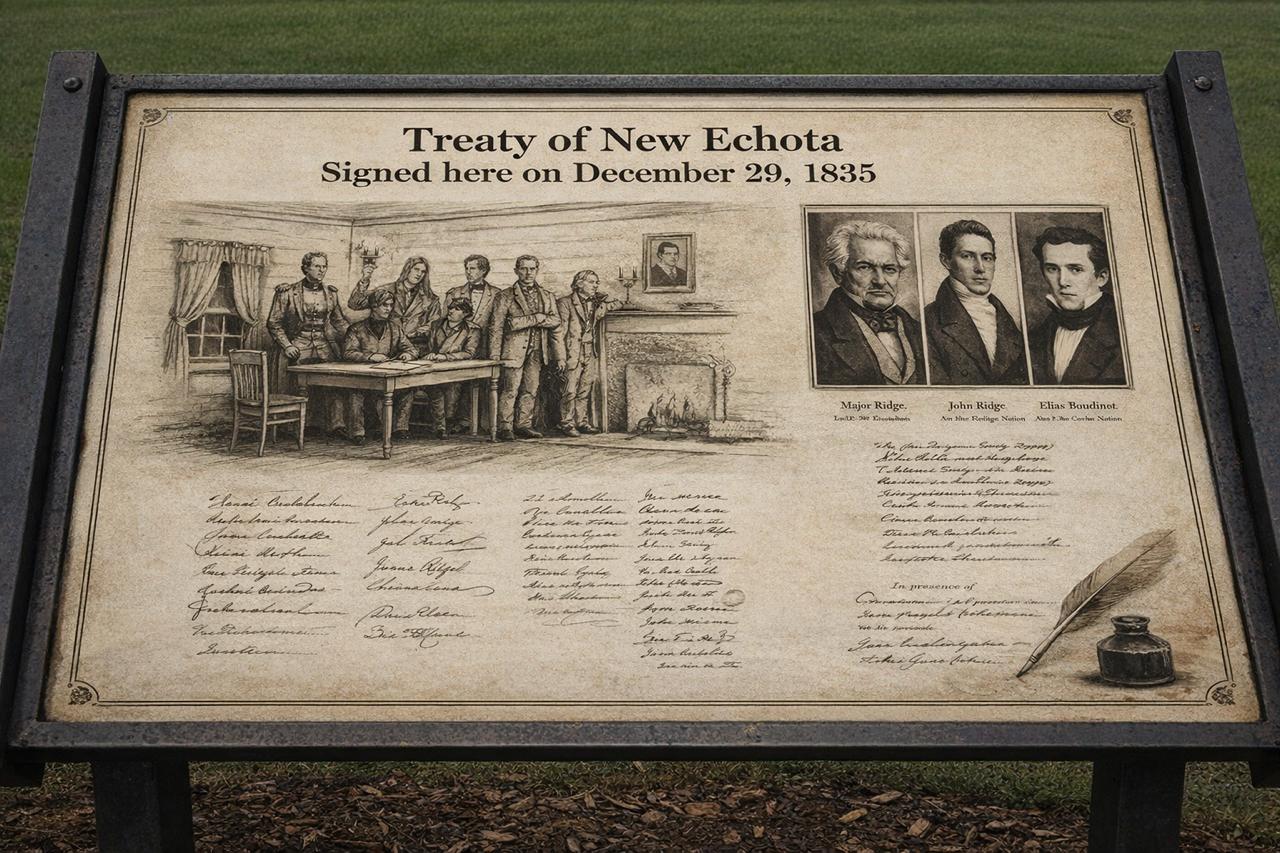

On 29 December 1835, a legal treaty was concluded in the American state of Georgia, historically known as the Treaty of New Echota. This agreement is regarded as one of the most controversial and troubling chapters in United States history, particularly in relation to land ownership, state authority, and the rights of Indigenous nations. By the early nineteenth century, the south eastern states of the United States, especially Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, had become centres of an expanding agricultural economy. Cotton cultivation, commonly referred to as the Cotton Economy, was growing rapidly, leading to an exceptional demand for fertile land. Large tracts of this land were owned by Indigenous communities, most notably the Cherokee Nation. Their continued presence was increasingly viewed as an obstacle to the American policy of westward territorial expansion. Within this context, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which provided the legal framework for the forced relocation of Indigenous peoples from east of the Mississippi River to lands further west. The Treaty of New Echota emerged as a direct outcome of this policy. The treaty was finalised on 29 December 1835 at New Echota, which was then the capital of the Cherokee Nation. Under its terms, the Cherokee ceded all their lands east of the Mississippi River to the United States government. This territory amounted to approximately seven million acres. In return, the government promised compensation of five million dollars and the allocation of alternative land in the west. This land lay within the area of present day Oklahoma, known at the time as Indian Territory. From a legal perspective, the most contentious aspect of the treaty concerned the issue of representation. The agreement was not signed by the elected leadership or the national council of the Cherokee Nation. Instead, it was endorsed by a small political faction, later known as the Ridge Party, whose members included Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Stand Watie. The principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, John Ross, along with the majority of the national council, rejected the treaty as invalid and contrary to the collective will of the people. The United States was represented in the negotiations by John F. Schermerhorn, a federal commissioner. Despite widespread opposition among the Cherokee population, the United States Senate ratified the treaty by a margin of just one vote. This ratification elevated the agreement to the status of federal law and paved the way for the use of state force. When a large proportion of the Cherokee people refused to comply with the treaty and abandon their ancestral lands, the United States military initiated a programme of forced removal. Between 1838 and 1839, thousands of Cherokee men, women, and children were gathered into detention camps and subsequently transported westwards. This episode became known in history as the Trail of Tears. Historical records indicate that approximately sixteen thousand Cherokee individuals were forcibly displaced from their homelands. The journey covered an average distance of twelve hundred miles and was undertaken on foot, by riverboats, and with limited means of transport. Severe weather conditions, inadequate food supplies, disease, and poor administration resulted in the deaths of an estimated four thousand people. In the Cherokee language, this journey is remembered as Nu na da ut sun y, meaning the place where they cried. After arriving in the west, the Cherokee Nation re established its political and social institutions in Oklahoma. Tahlequah was designated as the new capital, and systems of constitutional governance, courts, educational institutions, and newspapers were rebuilt. Nevertheless, their legal ownership of their former eastern lands was considered permanently extinguished. The legacy of this treaty has not entirely faded in the modern era. In 2020, the United States Supreme Court, in the case of McGirt v. Oklahoma, affirmed that large parts of Oklahoma legally remain tribal reservation land, as earlier treaties had never been formally revoked. This ruling carried significant implications for land rights, jurisdiction, and property law. [img:Images/2nd-image-29-dec.jpeg | desc:The Treaty of New Echota and the subsequent forced removal of the Cherokee people have been the subject of numerous serious documentary films and historical reconstructions based on official records and archival evidence. Notable among these are Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy and the PBS series We Shall Remain, which examine the legal and political consequences of the Indian Removal Act and the Treaty of New Echota. These works illustrate how treaties and federal policy were used to reshape patterns of land ownership and population geography. ] The Treaty of New Echota has been included in the Syed Shayan Real Estate Archives to serve as a reminder of how state policy, legal instruments, and economic interests can combine to dispossess ordinary people of their land.