Syed Shayan Real Estate Archive

From Real Estate History

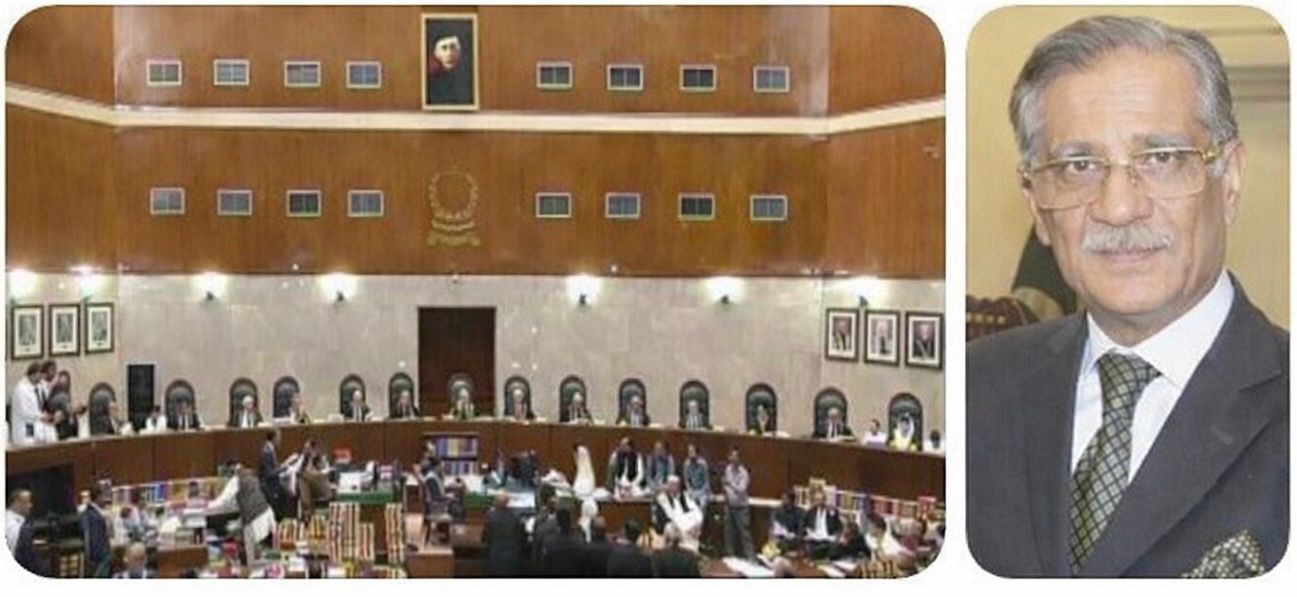

On 11 December 2018, the Supreme Court of Pakistan, under the leadership of then Chief Justice Mian Saqib Nisar, imposed a strict and highly unusual restriction on the transfer, lease, and allotment of land in Sindh. The court directed that until the provincial land revenue record was fully computerised, no allotment, lease, or transfer of government land would be permitted.

The impact of the order was immediate and far reaching. Across Sindh, land transfer activity in revenue offices came almost to a complete standstill. Alongside government land, transactions involving privately owned property were also slowed or suspended, largely due to fear and the absence of clear administrative guidance. In major cities, including Karachi, property buying and selling abruptly stalled. Files remained trapped in revenue offices, investors were forced into prolonged waiting, and uncertainty spread rapidly through the market. This situation persisted not for days or weeks, but for several months, effectively paralysing the real estate system, even though the court’s stated objective was to prevent the misuse of government land rather than to freeze the market altogether.

The stated purpose of the order was to curb illegal occupation of state land, politically motivated allotments, and the long standing lack of transparency within Sindh’s revenue system. In practice, however, these objectives were not achieved. Despite the clarity of the judicial directive, full computerisation of land records did not take place. The provincial government failed to develop a workable implementation framework, and following the retirement of the Chief Justice, the issue gradually slipped out of the government’s priorities. After several months of stagnation, the market partially reverted to its earlier functioning, and the order ultimately came to be remembered not as a reform but as a failed experiment in Pakistan’s real estate history.

As of 11 December 2026, eight years have passed since the order was issued, yet the fundamental question remains unanswered: what was the practical outcome of this directive? The reality is that Sindh’s land record has still not been comprehensively computerised. Some limited and largely symbolic measures were undertaken, but these neither expanded across the province nor evolved into a coherent and legally reliable digital system.

In rural Sindh, the patwari system continues to dominate, relying on manual registers. In urban areas, the record of rights and the registration system remain structurally disconnected. As a result, forgery, double registration, and land disputes persist. Had land records genuinely been computerised, citizens would not still be required to repeatedly visit revenue offices for ownership records, mutations, and transfers, nor would illegal occupation and fraudulent allotments continue to thrive.

The decision also raises a broader institutional question: whether the Chief Justice fully appreciated the ground reality that province wide computerisation of land records is a long, complex, and multi generational process. In a province such as Sindh, where millions of acres of agricultural and urban land are involved, where decades old manual records exist, and where long standing disputes, the goth system, informal settlements, and parallel ownership claims prevail, full digitisation inevitably requires many years rather than a matter of weeks.

From a real estate perspective, the decision suffered from three fundamental weaknesses. First, the court imposed an administrative condition without providing a timeline, allocating resources, or establishing a realistic framework for implementation. Second, while issuing a decision of a policy nature, the court failed to give binding directions to the institutions responsible for execution. Third, when the market froze, no interim legal or administrative mechanism was provided to manage the transition. As a result, neither reform nor systemic improvement followed, and uncertainty deepened.

Legally, the order was limited to government land. Private land transactions did not fall within its scope, and the court did not direct that buying and selling between private individuals should be halted. In practice, however, the outcome was very different. Because the revenue system in Sindh manages both government and private land through the same administrative structure, revenue officials, fearing contempt proceedings, also halted or severely slowed private land transfers. Consequently, the real estate market as a whole effectively came to a standstill

▪️Syed Shayan Real Estate Archive

▪ Reference(s):

11 دسمبر 2018 کو سپریم کورٹ آف پاکستان نے اس وقت کے چیف جسٹس میاں ثاقب نثار کی سربراہی میں سندھ میں زمینوں کے انتقال، لیز اور الاٹمنٹ پر ایک سخت اور غیر معمولی پابندی عائد کی، جس کے تحت یہ حکم دیا گیا کہ جب تک صوبے کا لینڈ ریونیو ریکارڈ مکمل طور پر کمپیوٹرائز نہیں ہو جاتا، سرکاری زمین کی کوئی الاٹمنٹ، لیز یا انتقال نہیں کیا جائے گا۔

اس عدالتی حکم کے فوراً بعد سندھ بھر کے ریونیو دفاتر میں زمینوں کے انتقال کا عمل تقریباً رک گیا۔ سرکاری زمین کے ساتھ ساتھ خوف اور غیر واضح ہدایات کے باعث نجی زمینوں کے انتقال بھی سست یا معطل ہو گئے۔ کراچی سمیت بڑے شہروں میں پراپرٹی کی خرید و فروخت جمود کا شکار ہو گئی، فائلیں دفاتر میں اٹک گئیں، سرمایہ کار انتظار میں بیٹھ گئے اور مارکیٹ میں شدید غیر یقینی کیفیت پیدا ہو گئی۔ یہ صورتحال چند دنوں یا ہفتوں تک محدود نہ رہی بلکہ مہینوں تک جاری رہی، جس کے نتیجے میں رئیل اسٹیٹ کا پورا نظام عملی طور پر مفلوج ہو گیا، حالانکہ عدالت کا مقصد پوری مارکیٹ کو بند کرنا نہیں بلکہ سرکاری زمین کے غلط استعمال کو روکنا تھا۔

بظاہر اس حکم کا مقصد سرکاری زمینوں پر غیر قانونی قبضوں، سیاسی بنیادوں پر الاٹمنٹ اور غیر شفاف ریونیو نظام کا خاتمہ تھا، مگر عملی طور پر یہ مقاصد حاصل نہ ہو سکے۔ واضح عدالتی حکم کے باوجود لینڈ ریکارڈ کی مکمل کمپیوٹرائزیشن نہ ہو سکی، صوبائی حکومت کوئی مؤثر فریم ورک تشکیل نہ دے سکی، اور چیف جسٹس کی ریٹائرمنٹ کے بعد یہ معاملہ حکومتی ترجیحات سے باہر ہو گیا۔ چند ماہ بعد مارکیٹ جزوی طور پر پرانے انداز میں چلنے لگی، اور یوں یہ حکم اصلاح کے بجائے پاکستان کی رئیل اسٹیٹ تاریخ میں ایک ناکام تجربہ بن کر رہ گیا۔

آج 11 دسمبر 2026 ہے۔ اس عدالتی فیصلے کو آٹھ برس گزر چکے ہیں، مگر بنیادی سوال اب بھی موجود ہے کہ اس حکم کا عملی انجام کیا ہوا؟ حقیقت یہ ہے کہ آج بھی سندھ کا لینڈ ریکارڈ مکمل سطح پر کمپیوٹرائز نہیں ہو سکا۔ کچھ محدود اور نمائشی اقدامات ضرور کیے گئے، مگر نہ وہ صوبہ گیر بن سکے اور نہ ہی ایک مربوط اور قابلِ اعتماد ڈیجیٹل نظام کی شکل اختیار کر پائے۔

دیہی سندھ میں آج بھی پٹواری نظام دستی رجسٹروں کے ساتھ غالب ہے، جبکہ شہری علاقوں میں ریکارڈ آف رائٹس اور رجسٹری کا نظام باہم منسلک نہیں ہو سکا، جس کے باعث جعل سازی، ڈبل رجسٹری اور زمینوں کے تنازعات بدستور موجود ہیں۔ اگر لینڈ ریکارڈ واقعی کمپیوٹرائز ہو چکا ہوتا تو شہری کو فرد، انتقال اور ملکیت کے لیے ریونیو دفاتر کے چکر نہ لگانے پڑتے اور نہ ہی قبضوں اور جعلی الاٹمنٹس کا بازار گرم رہتا۔

یہ عدالتی فیصلہ اس سوال کو بھی جنم دیتا ہے کہ کیا چیف جسٹس اس زمینی حقیقت سے ناواقف تھے کہ پورے صوبے کی زمینوں کی کمپیوٹرائزیشن ایک طویل، پیچیدہ اور کثیر النسلی عمل ہے۔ سندھ جیسے صوبے میں، جہاں لاکھوں ایکڑ زرعی و شہری زمین، دہائیوں پر محیط دستی ریکارڈ، پرانے تنازعات، گوٹھ سسٹم اور متوازی ملکیتی دعوے موجود ہوں، وہاں زمینوں کو مکمل طور پر ڈیجیٹائز کرنے میں کئی سال درکار ہوتے ہیں، نہ کہ چند ہفتے۔

رئیل اسٹیٹ کے تناظر میں اس فیصلے کی تین بنیادی خامیاں تھیں: عدالت نے بغیر ٹائم لائن، وسائل اور عمل درآمد کے فریم ورک کے ایک انتظامی شرط عائد کر دی؛ پالیسی نوعیت کا فیصلہ دے کر ان اداروں کو واضح ہدایات نہ دیں جو اس پر عملدرآمد کے ذمہ دار تھے؛ اور مارکیٹ کے منجمد ہونے کی صورت میں کوئی عبوری قانونی راستہ فراہم نہ کیا۔ نتیجتاً نہ اصلاح ہوئی اور نہ نظام بہتر، بلکہ بے یقینی میں اضافہ ہوا۔

قانونی طور پر یہ حکم صرف سرکاری زمین تک محدود تھا اور نجی زمین کے سودے اس کی زد میں نہیں آتے تھے، مگر چونکہ سندھ میں سرکاری اور نجی زمین کا ریکارڈ ایک ہی ریونیو نظام کے تحت چلتا ہے، اس لیے ریونیو افسران نے توہینِ عدالت کے خوف سے نجی زمینوں کے انتقال بھی روک دیے یا انتہائی سست کر دیے۔ یوں عملی طور پر پوری رئیل اسٹیٹ مارکیٹ بند ہو گئی۔

▪️ سید شایان ریئل اسٹیٹ آرکائیو

On November 22, 1991, the Punjab Public Health Engineering Department launched a major rural water supply rehabilitation program targeting villages located along major canal systems in districts including Vehari, Lodhran, Jhang, and Muzaffargarh. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, canal-adjacent villages faced declining water quality due to...

Read More →

The structure known globally today as Burj Khalifa was originally conceived and launched under the name Burj Dubai. An important and deliberate aspect of its history is that the inauguration was scheduled for 4 January 2010 to coincide with the anniversary of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum’s accession as Ruler of Dubai. On 4 January 2006,...

Read More →

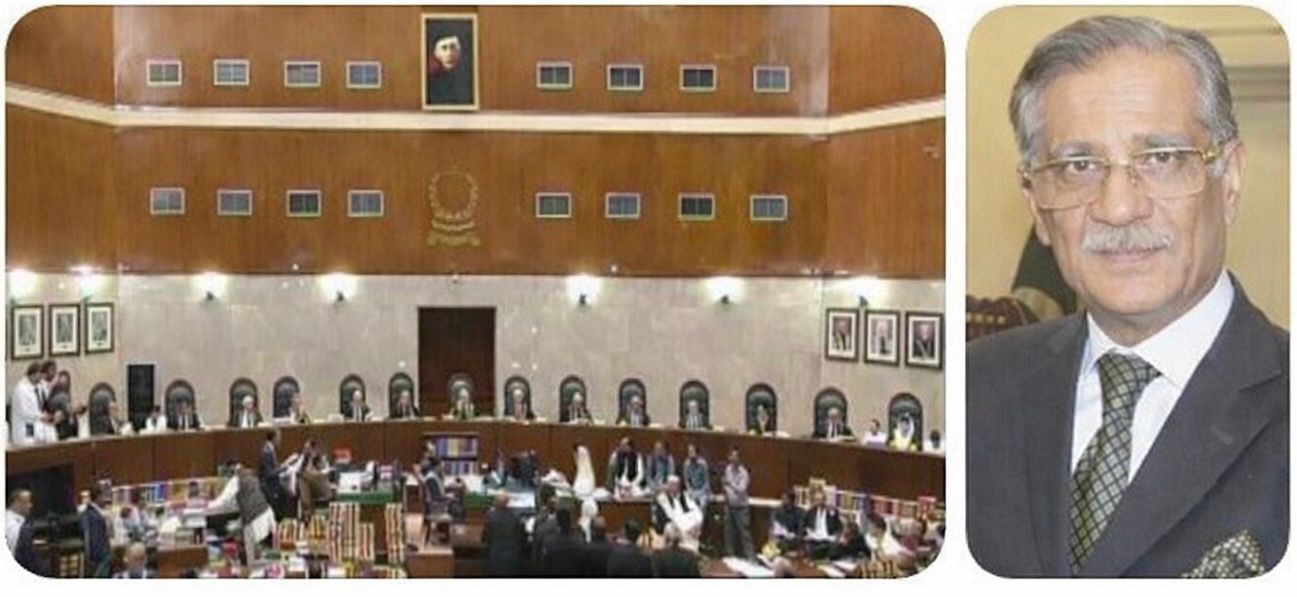

On 1 January 1959, the Cuban Revolution succeeded and Fidel Castro assumed power. It was a day that dealt one of the most severe blows in modern history to the concept of private property and real estate. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, vast swathes of land, residential housing, commercial buildings, hotels, and industrial assets a...

Read More →

On October 21, 1966, the Aberfan disaster occurred in Wales when a colliery spoil tip collapsed onto the village, killing 144 people including 116 children. This tragic event exposed critical failures in mining waste management and land use planning near populated areas. The disaster led to comprehensive reforms in mining regulations, waste disposa...

Read More →

The structure of the world map and globe as they are recognised today is fundamentally rooted in the decisions taken following the Paris Peace Conference, which began on 18 January 1919. Prior to the conference, much of the world was organised under a limited number of vast imperial systems. These included the Ottoman Empire, extending across Asia...

Read More →

The acquisition of land for the Model Town Society was one of the most remarkable and spirited chapters in its early history. Dewan Khem Chand and his...

Between 1921 and 1924, the land for Model Town Lahore was acquired in successive phases. The process began in 1921, shortly after the establishment of...

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!