From Real Estate History

30 December

East Asia: Cities, Land

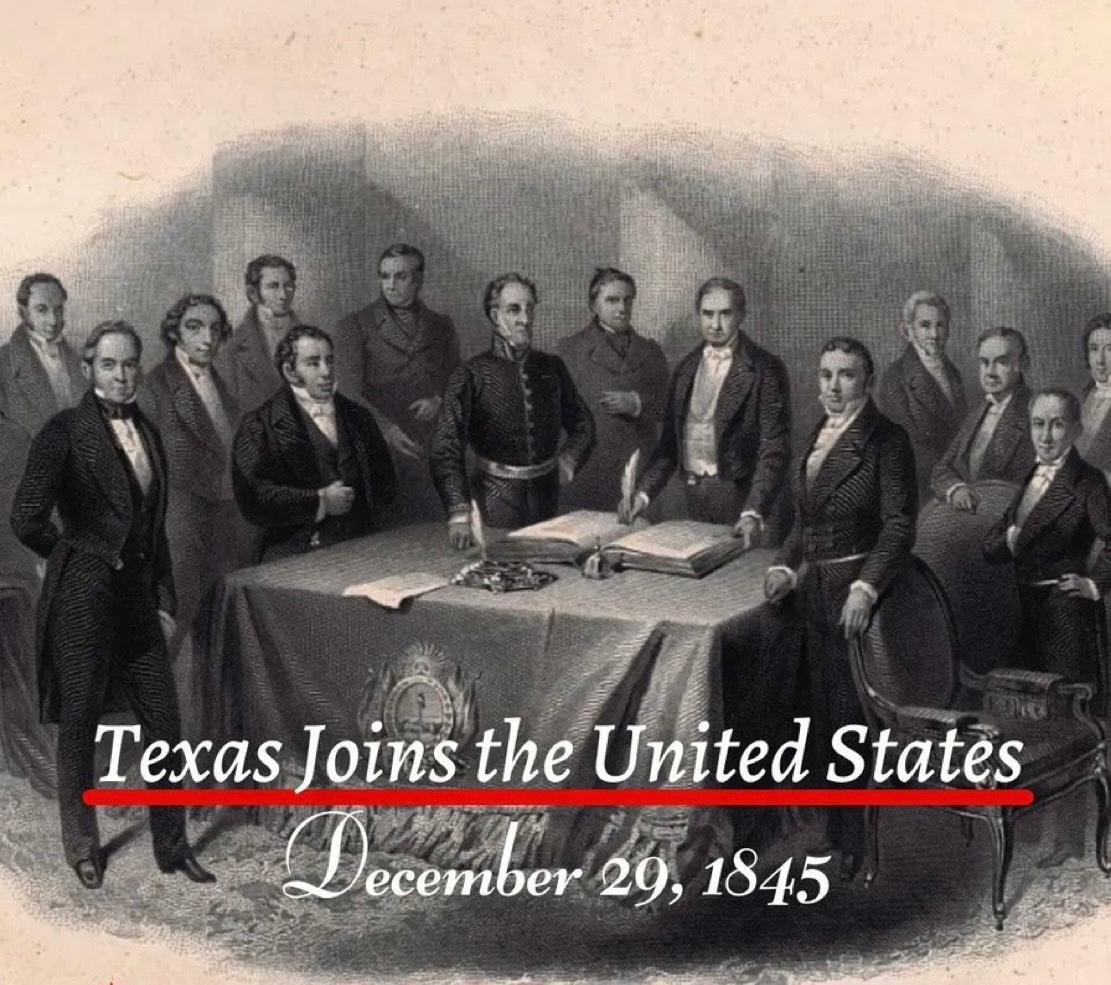

The Annexation of Texas to the United States

On 29 December 1845, Texas formally became the twenty eighth state of the United States. This event was not merely a political decision. It marked an extraordinary turning point in the global history of land ownership and real estate. As a result of this single day’s decision, approximately 259000 square miles, or nearly 695000 square kilometres, came under the jurisdiction of the American federal system. Texas held a unique position because it had previously existed as an independent republic. The land was already settled. Agriculture was actively practised. Claims of private as well as communal ownership were firmly in place. When Texas was annexed by the United States, all these lands were brought under the American constitutional and legal framework in a single moment. This transition reshaped land registration, land claims, agricultural ownership, and future urban planning within an entirely new framework influenced by American legal culture. Concepts of ownership, legal documentation, boundary demarcation, and patterns of urban expansion shifted from local traditions to align with the federal American system. The historical importance of this annexation is further underscored by the fact that it represented the largest territorial addition ever gained through the admission of a sovereign state into the United States. At the time, the area exceeded that of several European countries and opened the path for the expansion of the American property market towards the southern and western regions. In subsequent decades, these lands formed the foundation for vast agricultural estates, railway networks, industrial centres, and newly established cities. One of the most significant outcomes of Texas’s annexation for the United States was the acquisition of an extensive coastline, providing strong and direct access to the Gulf of Mexico. This geographical transformation also produced a broader economic benefit for landlocked states. The development of ports along the Texas coast created new and more accessible routes for the agricultural and industrial output of inland regions to reach global markets. Over time, as expansive railway networks and integrated river systems connected these landlocked states to the Texas coastline, interior regions became part of the global trade system. In this way, the annexation of Texas emerged as a gradual yet profoundly significant milestone in the overall economic growth of the United States.

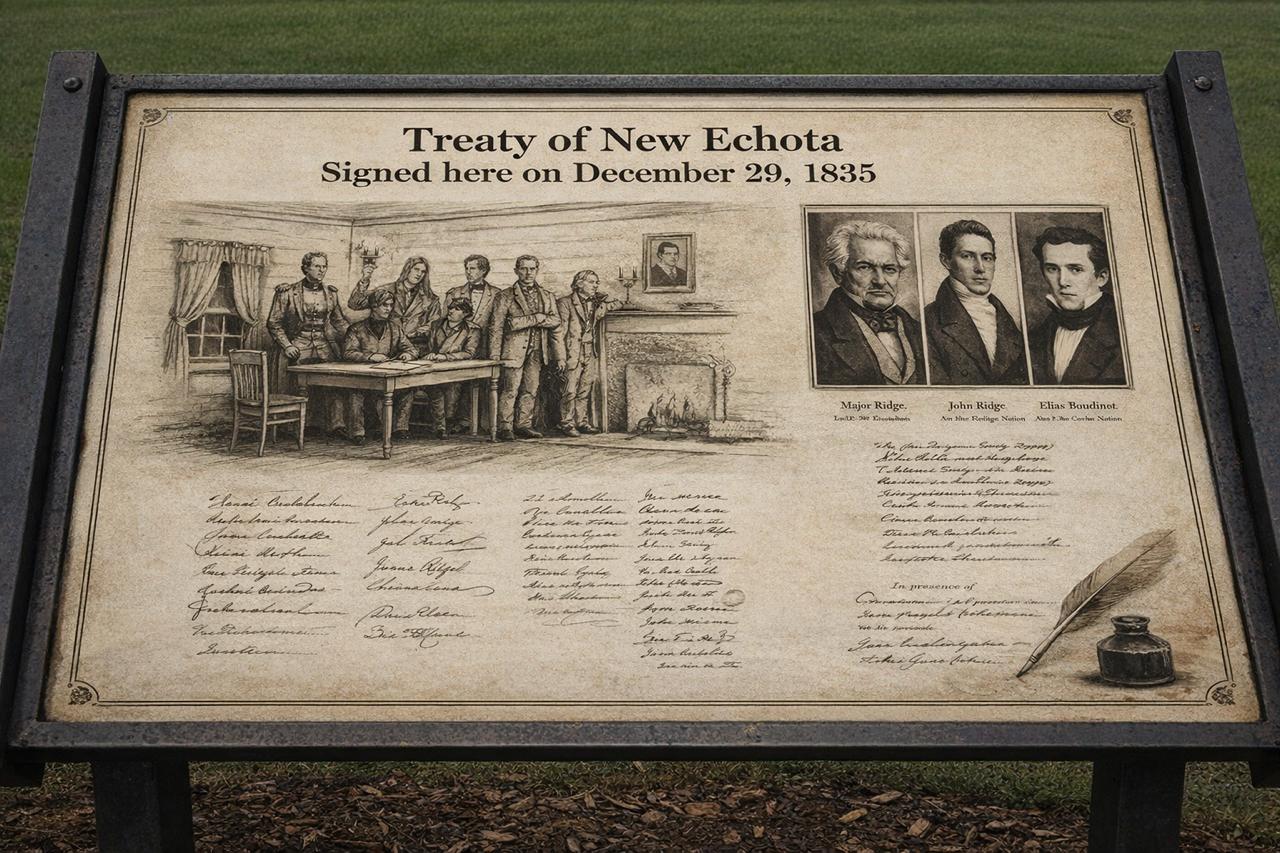

Treaty of New Echota When a minority group negotiated away an entire nation and its land

On 29 December 1835, a legal treaty was concluded in the American state of Georgia, historically known as the Treaty of New Echota. This agreement is regarded as one of the most controversial and troubling chapters in United States history, particularly in relation to land ownership, state authority, and the rights of Indigenous nations. By the early nineteenth century, the south eastern states of the United States, especially Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, had become centres of an expanding agricultural economy. Cotton cultivation, commonly referred to as the Cotton Economy, was growing rapidly, leading to an exceptional demand for fertile land. Large tracts of this land were owned by Indigenous communities, most notably the Cherokee Nation. Their continued presence was increasingly viewed as an obstacle to the American policy of westward territorial expansion. Within this context, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which provided the legal framework for the forced relocation of Indigenous peoples from east of the Mississippi River to lands further west. The Treaty of New Echota emerged as a direct outcome of this policy. The treaty was finalised on 29 December 1835 at New Echota, which was then the capital of the Cherokee Nation. Under its terms, the Cherokee ceded all their lands east of the Mississippi River to the United States government. This territory amounted to approximately seven million acres. In return, the government promised compensation of five million dollars and the allocation of alternative land in the west. This land lay within the area of present day Oklahoma, known at the time as Indian Territory. From a legal perspective, the most contentious aspect of the treaty concerned the issue of representation. The agreement was not signed by the elected leadership or the national council of the Cherokee Nation. Instead, it was endorsed by a small political faction, later known as the Ridge Party, whose members included Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Stand Watie. The principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, John Ross, along with the majority of the national council, rejected the treaty as invalid and contrary to the collective will of the people. The United States was represented in the negotiations by John F. Schermerhorn, a federal commissioner. Despite widespread opposition among the Cherokee population, the United States Senate ratified the treaty by a margin of just one vote. This ratification elevated the agreement to the status of federal law and paved the way for the use of state force. When a large proportion of the Cherokee people refused to comply with the treaty and abandon their ancestral lands, the United States military initiated a programme of forced removal. Between 1838 and 1839, thousands of Cherokee men, women, and children were gathered into detention camps and subsequently transported westwards. This episode became known in history as the Trail of Tears. Historical records indicate that approximately sixteen thousand Cherokee individuals were forcibly displaced from their homelands. The journey covered an average distance of twelve hundred miles and was undertaken on foot, by riverboats, and with limited means of transport. Severe weather conditions, inadequate food supplies, disease, and poor administration resulted in the deaths of an estimated four thousand people. In the Cherokee language, this journey is remembered as Nu na da ut sun y, meaning the place where they cried. After arriving in the west, the Cherokee Nation re established its political and social institutions in Oklahoma. Tahlequah was designated as the new capital, and systems of constitutional governance, courts, educational institutions, and newspapers were rebuilt. Nevertheless, their legal ownership of their former eastern lands was considered permanently extinguished. The legacy of this treaty has not entirely faded in the modern era. In 2020, the United States Supreme Court, in the case of McGirt v. Oklahoma, affirmed that large parts of Oklahoma legally remain tribal reservation land, as earlier treaties had never been formally revoked. This ruling carried significant implications for land rights, jurisdiction, and property law. [img:Images/2nd-image-29-dec.jpeg | desc:The Treaty of New Echota and the subsequent forced removal of the Cherokee people have been the subject of numerous serious documentary films and historical reconstructions based on official records and archival evidence. Notable among these are Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy and the PBS series We Shall Remain, which examine the legal and political consequences of the Indian Removal Act and the Treaty of New Echota. These works illustrate how treaties and federal policy were used to reshape patterns of land ownership and population geography. ] The Treaty of New Echota has been included in the Syed Shayan Real Estate Archives to serve as a reminder of how state policy, legal instruments, and economic interests can combine to dispossess ordinary people of their land.

The Louisiana Purchase: the largest land transaction in global real estate history, formally transferred on this day

20 December 1803 stands as a defining date in the global history of real estate and land agreements. It not only reshaped the concept of land acquisition but also introduced a new dimension to state expansion, geopolitics, and the strategic value of land. This event is historically known as the Louisiana Purchase. The Louisiana Purchase was not a conventional commercial transaction within a real estate market. Rather, it was a sovereign-to-sovereign land transfer, involving the sale and transfer of territory from one state to another. The transaction was executed without reference to market valuation mechanisms and was driven entirely by political and strategic considerations. For this reason, it is regarded as the largest land transaction in recorded history and, on technical grounds, may also be described as the largest real estate deal ever concluded. Although the Louisiana Purchase treaty had been agreed earlier, on 30 April 1803 in Paris, the decisive event occurred on 20 December 1803, when France formally transferred practical control of the vast Louisiana territory to the United States of America. The United States was represented by Robert Livingston and James Monroe, while France was represented by François Barbé-Marbois, acting on behalf of the government of Napoleon Bonaparte. The formal ceremony of transfer took place in New Orleans, completing what is widely recognised as the largest territorial transfer in history. As a direct consequence of the Louisiana Purchase, the United States doubled its geographical size in a single act, while France relinquished control of a distant territory in order to concentrate on its European priorities. Under the terms of the agreement, the United States acquired approximately 828,000 square miles of land, equivalent to around 2.1 million square kilometres. By comparison, this area was roughly two and a half times larger than the present land area of Pakistan. The territory was acquired for 15 million US dollars, an amount that equates to only a few cents per acre by modern standards. In the history of global real estate, the acquisition of such an immense territory at such a nominal price, yet with such profound strategic significance, remains without precedent. The significance of the Louisiana Purchase extended far beyond its price or size. The agreement fundamentally reshaped the future geographical, economic, and political structure of the United States. As a result of this territorial acquisition, fifteen American states later emerged from the Louisiana territory, including Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Texas. These regions played a decisive role in strengthening agricultural production, industrial expansion, and internal trade, transforming the United States into a continental power. From a geographical perspective, most of the acquired territory was landlocked, lacking direct access to an ocean coastline. However, the true strategic value of the acquisition lay in the United States gaining full control over the Mississippi River system and its entire basin, which ultimately connects to the Gulf of Mexico. This acquisition established a strong internal geographical backbone for the United States, later enabling westward expansion towards the Pacific coast. Politically, the purchase represented a major decision for President Thomas Jefferson, as the United States Constitution contained no explicit provision for the acquisition of foreign territory. Nevertheless, guided by national interest, future expansion, and control of the Mississippi River, the transaction was completed and later came to be regarded as one of the most prudent decisions in American history. Historically, the territory of Louisiana was a product of European imperial expansion. In 1682, the French explorer Robert de La Salle claimed the Mississippi River basin for France and named the territory Louisiana in honour of King Louis XIV. This claim was not based on the consent of indigenous populations but on a colonial doctrine that treated discovery as the basis of ownership, with land regarded as an expression of sovereign land ownership. France organised the territory as a colonial possession, but following the Seven Years’ War in 1763, Louisiana was transferred to Spain. Later, in 1800, under the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso, Spain returned Louisiana to France, placing the territory legally under French control at the time of sale. In practice, however, neither Spain nor France succeeded in establishing durable and effective administrative control over this vast region. Ongoing Napoleonic wars in Europe, acute financial pressures, and the increasing difficulty of sustaining overseas colonial territories proved decisive for France. Under these conditions, Napoleon Bonaparte chose to sell Louisiana, securing immediate financial resources while simultaneously strengthening the United States as a counterbalance to British power. In this way, a fragile colonial possession was transformed into the largest land transaction in history. This day therefore serves as a reminder of the multi-dimensional strategic thinking of European powers, which often extended control far beyond their practical capacity to govern. Such territorial decisions were shaped not only by military power, but by financial capability, naval security, global trade interests, and long-term political balance. In the case of Louisiana, France chose strategic withdrawal over the maintenance of an unsustainable and costly possession. In this context, 20 December 1803 symbolises the reality that land decisions are rarely about geography alone; they are decisions of time, power, foresight, and statecraft. At times, strategic retreat itself becomes the force that shapes the direction of history.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)