From Real Estate History

30 December

International Politics

The Florida Land Boom of the 1920s The Florida Land Boom is widely regarded as the first major speculative bubble of the modern real estate era, a period when land could change hands several times within a single day, each transaction multiplying its price

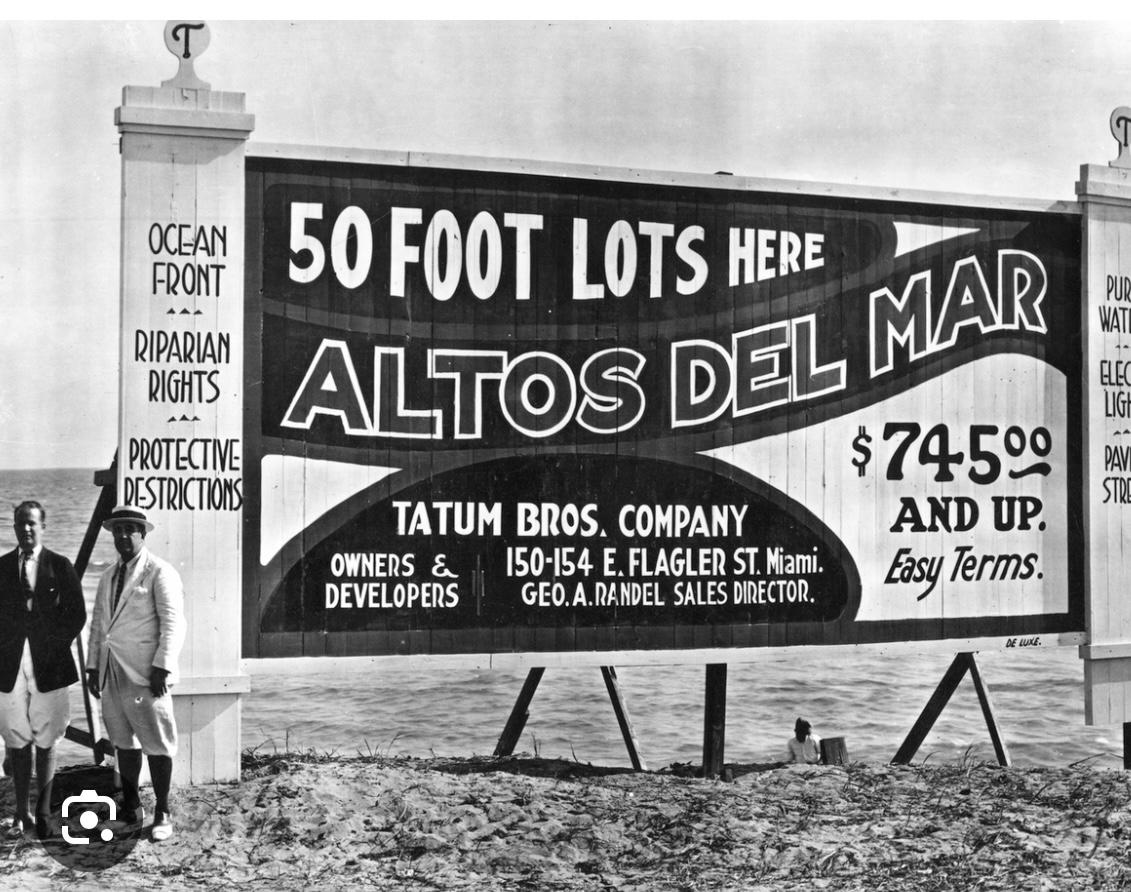

Exactly one century ago, on 23 December 1925, the most famous real estate phenomenon in American history stood at its absolute peak. Across Florida, particularly in Miami and Palm Beach, the purchase of land had transformed into a national obsession. The promise was simple and intoxicating: fortunes could be made overnight. At the height of the boom, even the smallest plots in virtually any district of these cities could double in value within hours. Buyers routinely paid advances without inspecting the land, and in many cases plots were resold for profit even before formal registration was completed. Real estate agents, investors, and ordinary citizens alike were swept into the frenzy, united by a shared conviction that prices would never fall. Contemporary newspaper reports from December 1925, most notably the 23 December edition of The Miami Herald, describe scenes bordering on the extraordinary. Despite the Christmas holidays, thousands queued to purchase land. Railway stations, ports, and land offices were overwhelmed, while civic systems struggled to cope with the sheer volume of speculative activity. Economic historians have since identified this episode as the first great real estate bubble of the modern age. Land values were no longer determined by housing needs or economic fundamentals, but by speculation, rumour, and the pursuit of rapid profit. The boom, however, proved unsustainable. In 1926, a devastating hurricane struck Florida, destroying vast areas and shattering investor confidence almost overnight. Economic strains quickly followed, land prices collapsed with remarkable speed, and the Florida Land Boom, once celebrated worldwide as a symbol of opportunity and prosperity, became a lasting cautionary tale in real estate history. When examined plainly, the underlying story is unmistakably clear. Following the First World War, the United States experienced a surge in wealth. Automobiles became commonplace, railways and advertising compressed distances, and Florida was marketed as a dreamland where sunshine, oceanfront living, and rapidly expanding cities promised universal prosperity. In Miami and Palm Beach in particular, land was no longer acquired for settlement but for immediate resale. Plots were purchased without inspection, without maps, and often without any understanding of location, driven solely by hearsay and expectations of rising prices. A plot acquired in the morning could pass through several owners by evening. Land ceased to function as an asset rooted in utility and instead became a certificate of anticipated wealth, sustained by the collective belief that prices could only rise. The fundamental weakness of the system lay in the absence of genuine end users. Most buyers had no intention of building homes or establishing communities. They were merely waiting for the next purchaser. Once the flow of new buyers slowed, the structure began to falter. By late 1925, rail networks were paralysed, not by building materials, but by the transport of land documents. Banks began to restrict lending, buyers disappeared, and for the first time prices stagnated. These were the early signs of collapse.[img:Images/2nd-image-23-dec1.jpeg | desc:This board is a striking example of the deceptive advertising that characterised the Florida Land Boom. Swamp land and waterlogged areas were promoted as “reclaimed land” and boldly described as “the richest soil in the world.” The purpose of such language was not to reflect the land’s actual condition, but to convince buyers that an immediate purchase would yield rapid profits. In reality, most of these plots were neither properly drained nor suitable for housing or cultivation. Yet slogans such as “buy now at ground floor prices” were used to intensify speculation. This form of misleading promotion played a central role in inflating the Florida Land Boom into a speculative bubble, which ultimately left thousands of investors facing heavy financial losses.] Two decisive developments in 1926 rendered the decline irreversible. First, a powerful hurricane struck Miami, destroying thousands of structures, crippling ports, and exposing the reality that the city had been sold far faster than it had been built, secured, or prepared. Second, confidence among banks and developers evaporated. As payments ceased and instalments defaulted, the very documents once regarded as wealth became liabilities. Countless individuals who had purchased land through borrowed funds lost everything. The outcome was severe. In many areas, land values fell by fifty to seventy percent. Thousands of projects were abandoned, banks failed, and Florida’s economy was set back for years. Crucially, all of this occurred three years before the Great Depression of 1929. For this reason, scholars consistently identify the Florida Land Boom as the first modern speculative real estate bubble, containing all the defining elements later repeated across the world: purchases driven by rumour, the absence of real demand, faith in effortless profit, and the sudden collapse of systemic confidence. The enduring lesson of the Florida Land Boom is unmistakable. Land was stripped of its function as shelter and long-term asset and transformed into a vehicle for rapid speculation. When buyers place their faith solely in the next buyer and abandon underlying use, prices may rise, but they cannot endure. This principle lies at the heart of why the episode is still taught in universities across the United States and beyond, within disciplines such as real estate studies, economics, urban planning, and finance. Students are shown how speculation, market psychology, and the abandonment of economic fundamentals combine to inflate bubbles, and how those same forces ultimately precipitate collapse. Estimates of the financial losses caused by the Florida Land Boom have varied across historical accounts, and no single official figure exists. Nevertheless, economic historians have established a broadly accepted consensus range. Historical records indicate that during the early 1920s, speculative land transactions in Florida reached an estimated total value of six to seven billion US dollars in 1920s terms. When the bubble collapsed between 1925 and 1926, direct and indirect losses are estimated at approximately two billion US dollars in contemporary values. This figure appears consistently in American economic history and is regarded as a confirmed historical estimate. Adjusted for inflation, these losses equate to approximately thirty to thirty-five billion US dollars in present-day terms. It is important to note that the damage extended far beyond declining land prices. It encompassed widespread bank failures, the cancellation of construction projects, loan defaults, and the prolonged paralysis of Florida’s state economy.

The State Recognition of Affordable Housing as a Public Right in France

In the aftermath of the First World War, Europe faced widespread devastation. Millions of homes had been destroyed, while soldiers returned from the front to cities unable to absorb them. In Britain, this moment gave rise to the slogan “Homes Fit for Heroes”, encapsulating a growing belief that postwar reconstruction demanded more than physical rebuilding. Within this context, the French government decree issued on 22 December 1924, alongside Britain’s Wheatley Act of the same year, marked a decisive turning point in the history of housing and real estate. For the first time, the provision of housing was formally acknowledged as a public responsibility rather than a charitable or purely private concern. On 22 December 1924, France issued a formal governmental order that transformed the Loucheur Law from a legislative framework into an operational programme. This decree authorised, for the first time, the allocation of public funds specifically for affordable housing, enabled the acquisition and designation of land for residential development, and vested municipal authorities with clear mandates for construction and implementation. Through this administrative and financial framework, the state assumed the role of housing developer, explicitly recognising access to affordable housing as a public right. In the immediate aftermath of the decree, construction commenced under the model of Habitations à Bon Marché (HBM), representing France’s earliest systematic approach to affordable housing. In subsequent years, this framework evolved into the structured system of Habitations à Loyer Modéré (HLM), establishing regulated, low-rent public housing as a permanent feature of the urban landscape. The importance of this moment has endured. Contemporary debates around low-cost housing and social housing policy continue to draw upon the practical foundations laid by the decision of 22 December 1924. Following the issuance of the decree, land acquisition began in the outskirts of Paris for the development of garden cities and collective residential apartment blocks. Designed around principles of open space, natural light, greenery, and access to essential services, these schemes represented a significant departure from prevailing urban models. For the first time, it was formally asserted that low-income citizens were entitled not merely to shelter, but to dignified and adequate living conditions. This decision also established a new precedent for state intervention. While municipal and cooperative housing initiatives had existed on a limited scale prior to this period, it was within this framework that the state, for the first time at a national level, assumed responsibility for large-scale funding, land allocation, and construction. This model later informed social housing policies across Europe and, eventually, across much of the world. Today, as discussions continue in Pakistan and elsewhere regarding low-cost housing, access to housing for lower-income populations, and the role of state subsidy, their intellectual and practical origins can be traced to the decision of 22 December 1924. That moment reframed real estate from a purely investment-driven asset into an arena of social responsibility, positioning housing as a foundational element of the relationship between the state and its citizens.

Nazi Germany issues decree for the compulsory seizure of Jewish property

(Berlin) On 3 December 1938, the Nazi government enacted a severe state decree titled “Verordnung über den Einsatz des jüdischen Vermögens” (Regulation on the Use of Jewish Property), through which the forced sale of all residential, commercial and agricultural assets owned by Jewish citizens was formalised in law. Signed by Economics Minister Walther Funk and Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick, the order formed part of Adolf Hitler’s direct policy following Kristallnacht, aimed at removing Jews entirely from Germany’s economic, social and territorial life. Under this decree, Jewish property owners were compelled to sell all their holdings within a fixed period, with only “Aryan” non Jewish Germans permitted as purchasers. As a result, homes, shops and land were transferred at prices far below their actual market value, while a substantial portion of the proceeds was absorbed by the state through taxes and confiscatory measures. Remaining funds were deposited into government-controlled blocked accounts, to which former owners had no free access. A key provision prohibited Jews from acquiring any new real estate, residential rights, mortgages or land. Thus, while they were forced to relinquish their existing property, they were simultaneously denied the right to obtain any alternative accommodation, giving full legal support to the process of Aryanisation. (Aryanisation was the systematic Nazi policy under which Jewish homes, businesses, land, bank accounts and commercial assets were forcibly transferred to non-Jewish German “Aryans”.) This policy became a structured instrument of economic dispossession, depriving thousands of Jewish families of their homes and workplaces and pushing them into ghettos (ghettos being enclosed, prison-like quarters where Jews were segregated from the general population) and forced-labour camps. It represented one of the clearest violations of private property rights and a stark example of state driven expropriation. Following the end of the Second World War, Allied authorities repealed this decree and all anti-Jewish laws in 1945. Post war Germany subsequently enacted restitution and compensation statutes to restore confiscated properties or provide financial redress. Even today, the decree of 3 December 1938 remains a central historical reference point in international discussions on forced expropriation, private property rights and state abuse of authority.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)